“Bhutan needs to start from scratch.” In a meeting with Bhutan’s former prime minister Lotay Tshering in August last year, as his country sat on an inflection point post-pandemic, he shared that the country was shaking up its systems —from tourism to banking, corporate to judiciary. With the monarchy calling the shots in the Himalayan nation, a new government in power under Tshering Tobgay as PM is likely to follow the same diktat. In fact, soon after winning the general elections in January this year, Tobgay posted on X: “Bhutan is open for business!”.

The ambitious Mindfulness City project in Gelephu is at the centre of this restart. King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck announced the project during his national day address in December, and reportedly work is on in full swing to develop the special administrative region. India

Director general of tourism department Dorji Dhradhul told FE that the development strategy has three priorities —expansion of the energy sector; improving physical and digital connectivity, and upskilling people.

Covering an area of over 1,000 sq km in the east of Bhutan, a region that is currently neglected as the only international airport is at Paro on the western side, the economic hub aims to have sustainability and wellbeing at its centre. The king announced in his speech that as an economic hub, “the SAR will have the autonomy to formulate laws and policies that are needed. It will have executive autonomy and legal independence”. The objective is to establish an economic corridor through road and rail that will extend to Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia and Singapore in south-east Asia via India for import and export. To be developed by Danish Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), engineering firm Arup and development consultancy firm Cistri have been roped in for the futuristic city that will include an international airport, railway links to India, a hydroelectric dam for green energy and multiple spaces for education and scientific initiatives. Dhradhul told FE that the project will be funded through a range of domestic and international sources, saying that “active discussions are on for specific investments, but as they are under non-disclosure agreements, details cannot be shared currently”.

Interestingly, while it invites investors, Bhutan is clear that all businesses that will be a part of the SAR have to be in alignment with the country’s gross national happiness philosophy. Which means businesses like weapon manufacturing, etc, are not welcome. “Gelephu Mindfulness City is for companies whose purpose is compatible with the Gross National Happiness philosophy, that want their talents to live in a tight-knit ecological community that prioritises wellbeing, and companies that will contribute to sustainable development. We see these as positive criteria that will attract companies which have a compatible purpose, thus only companies that satisfy these requirements are invited to set up residencies,” says Dhradhul.

This applies not just to the SAR, but the entire country. All businesses need to be in accordance with the country’s environment and cultural traditions. Hazy at times, such policies are not exactly attractive for investors, which has resulted in a stagnant economy

This inevitably has led to a massive brain drain, accelerated post-pandemic. Youngsters are making a beeline for Australia, Canada and the UK for better academic and employment opportunities. A young couple seated next to me on the flight from Paro were headed to Delhi for a connecting flight to the UK. The woman had enrolled in a human resources management course, and the husband was accompanying her. They had no intention of returning, and the husband told me: “There is a herd mentality regarding emigration amongst the youth. Anyone not considering it is labelled a loser.” As per the Australian Bureau of Statistics, about 13,270 Bhutanese, most of them students, migrated to Australia in 2022-23. This accounts for 1.7% of Bhutan’s population.

Addressing this issue is a major objective of the Gelephu SAR. As the king said in his December speech: “I empathise with our youth who are at a crossroads. Given limited opportunities at home, they are faced with the challenging decision to move abroad for better incomes. Our immediate goal is for Bhutan to become a developed country. The Gelephu project is to enable you to return. In the meantime, please work hard and gain knowledge and skills. Your experience and exposure overseas will be invaluable for Bhutan as we build our future together.”

But will Gelephu end up becoming another project supported by India alone, or will it attract world-class companies from across the globe, only time will tell.

Tourism that’s high value, low volume

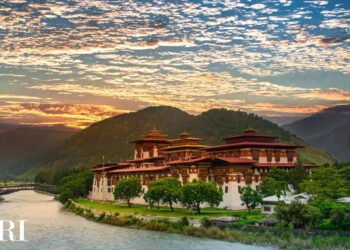

A few minutes drive from Punakha dzong in the Punakha valley, you stop by the Mo Chhu river beside a small bridge. Crossing over the rickety wooden bridge to the other side, you take a buggy ride through the thick forest, and arrive at a small traditional building nestled amid rice fields. When you enter the courtyard, surrounded by trees laden with avocado, pomegranate, and orange, you are welcomed to the Amankora. An uber luxury resort, this place has no shiny structures or glamorous lobbies. What you find instead are only 12 suites scattered amid the serene rice fields and orchards, with nothing and nobody around. Enjoy nature for $1,800 a night.

Or, get lost, literally, in the tented suites of the Pemako Punakha, which has only 21 tents nestled in the thick forest, each tent so distant from the other, you can’t ever run into your neighbours. This is the high value and low volume tourism Bhutan, also known as the last Shangri-La, boasts of. Nowhere in Bhutan do you see crowds or lines of vehicles. What you encounter instead are trees laden with apples lining the highways, verdant mountains, crystal clear waters, blue skies and pillowy white clouds. It is to experience all this that visitors from Europe and America pay up to $1,800 a night.

Interestingly, at the launch of a book on the northeast in Delhi a few months back, Union minister Hardeep Puri voiced ambitions of the region commanding $1,500 a night with niche tourism and hotels. While that seems a pipe dream for India, Bhutan has already achieved it.

Bhutan’s pristine nature is what enables it to offer this kind of tourism, with its high value low volume policy the key driver behind it. Call it audacity or a defiant bet, the country commands perhaps the world’s highest tourism fee at $100 per person per night, called the sustainable development fee (Indians pay just Rs 1,200 per person per night). Interestingly, this is half of the exorbitant $200 being charged post-pandemic in an over-calculative bid by the previous government. There are other strict rules as well, including mandatory use of guides. But while the government has always insisted on this policy, the tourism sector, especially the mid-value players, would rather have their cash registers ringing. When tourism exploded everywhere in the world after the reopening in 2022, with neighbouring India seeing record numbers, Bhutan got a very thin slice of the pie due to the high SDF. The tourism sector went up in arms, with hotels, guides and other tourist stakeholders voicing protests.

At the Pemako Thimphu, erstwhile Taj Tashi, general manager Christiane Doris Wasfy said in August 2023, “The government needs to make up its mind. Policies keep changing and the price is paid by the tourism sector.” By end-August, in a rethink of the tourism policy, the SDF was rolled back, albeit still remaining the world’s highest. And the Pemako, a hospitality brand owned by Bhutan’s largest private sector player—the Tashi Group—opened the doors of its luxury hotel in Punakha in December, well in time to welcome tourists this spring.

At the Tashi Namgay Resort in Paro, located right opposite the airport, the general manager lamented in late August that his bookings register was empty for the season. Post the revised SDF and new policies, he is a much happier man with a marked increase in bookings.

Indian hospitality major, the Indian Hotels Company

Other luxury brands like Six Senses, Como Uma are also present in the country, offering high-end hospitality. However, there are guidelines for hotels too. Tourism department director general Dorji Dhradhul says while there isn’t a direct cap on the number of hotels built, there are strict regulations on the architecture, location and impact of any new construction. “This is to ensure that new developments are in harmony with the surrounding environment and Bhutanese cultural aesthetics,” he says, adding, “There isn’t a categorical restriction on where hotels can be built, but the stringent building and environmental regulations indirectly dictate suitable locations. Hotels or resorts must fit within the natural and cultural landscape, avoiding ecologically sensitive zones or places of cultural importance. This might explain why only specific brands have a presence in the country.”

He said the idea is to attract discerning travellers who appreciate and respect Bhutan’s unique culture and pristine environment and are willing to pay a premium for the experience.

Dhradhul claims that Bhutan will reach pre-pandemic levels in tourism recovery by 2025. “The first half of 2023 was challenging for the industry, while the second half was much more productive. Some hotels and tour operators in Bhutan are flourishing, while others are still slower than pre-pandemic. It’s also a new business environment for them based on the changes in our tourism strategy, which allows hotels to actively promote themselves and solicit business directly,” he told FE.

Another factor that will surely benefit tourism is the steep reduction in air fares (by 43%) for SAARC nationals effective November 2023. Druk Air and Bhutan Airlines, the country’s two airlines, fly to Bhutan from Singapore, Thailand, India, Bangladesh

Looking south toward India

Sandwiched between two powerful but opposing countries, India and China, Bhutan’s economy depends on India for most things. One reason is that the border with China is snow-bound, and access is difficult. And, with the Indian government’s friendly policies toward the Himalayan nation, Bhutan has always looked south. India is the largest and most important trading partner for Bhutan, with electricity as the major import, pegged at Rs 2,443 crore in 2021.

India’s trade with Bhutan has tripled since 2014, from $484 million in 2014-15 to $1,422 million in 2021-22, which amounts to about 80% of Bhutan’s overall trade.

The Gelephu Mindfulness City development is also largely dependent on India. Before announcing the project in December, the Bhutanese king had met Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Delhi a month earlier and had been assured of India’s help to develop the economic hub. While an MoU to set up five rail links was signed in 2005 between the two countries, nothing had actually materialised. However, last year, before the Gelephu SAR was announced, external affairs minister S Jaishankar had told reporters in August 2023 that talks were on for a 57-km-long rail link between Kokrajhar in Assam and Gelephu in Bhutan. Even former PM Lotay Tshering told FE that experts from both sides had visited the sites and the rail links will happen “as soon as possible”. His office had shared that there was possibility for rail links at Samste, Phuentsholing and Samdrupjongkhar as well. These links will be an integral part of the SAR, connecting the rest of south-east Asia to Bhutan via India. Reportedly, India has also assured help in developing the international airport at Gelephu.

Says Dorji Dhradhul of department of tourism, “Bhutan and India have long had a unique and special friendship, and this will not change. Enhanced economic vitality in Bhutan will have a spillover effect on the region, raising opportunities for companies in north India and other locations to invest in the Mindfulness City, build partnerships with companies operating in the SAR and supply goods and services to companies operating and workers living in the city. Economic growth and vitality alongside the development of the Mindfulness City will strengthen social and cultural ties.”

Tshering had shared that his country was willing to welcome multinational businesses set up in India to Bhutan as well, saying they could offer skilled workers, and incentives, including tax breaks, for industries in education, science, information technology, etc.